Transcript, Episode 11: Kimmerians: The Beginning of the End

hpa was by no means an arrogant man. His rise to chieftain had not been easy. It had not been guaranteed. Teushpa was forced to contend with rivals and claimants. All of them were now ashes and corpses. He had to prove himself. During the great raid against the Phrygians, Teushpa led a pack of riders. They raided a number of villages and even attempted to join in the sacking of Gordion. He had been a noted leader back then, and years later, he’d proven himself as the chief of the western Kimmerians.

When news came to him of a new Assyrian ruler, an untested man named Esarhaddon, Teushpa knew it was his opportunity to lead the Kimmerians towards something greater. It would be vengeance. The memories of prior Assyrian invasions, of the murders of innocent Kimmerians, loomed large over Teushpa. And so, he made the fateful command. From their base in Cilicia, they rode south and eastward, into the lands of Assyria. For a time, they found victory after victory, pushing deeper and deeper into the enemy heartland.

And then, the Assyrian army met the Kimmerians with their full force.

And that was when Teushpa found himself under immense arrow fire. He roared at his riders, urging them to march forward. Several squads of horsemen fanned out in multiple directions. They would try to limit casualties by spreading out, and as they rode, they fired arrows into the Assyrian horde. They launched volley after volley after volley. They rode forward, and swiftly reared around before turning back, firing another volley here and another there.

It seemed to be going well. A few errant Assyrians rode forward and were quickly cut down. The vast majority of the Assyrian army began to falter and march backwards. Teushpa gestured at several riders, who then motioned to many others. This was the time to push on and force the Assyrians into a rout. He rode forward.

And then the Assyrian army opened up. Horsemen rode from the gaps. Teushpa looked to his right. One of his commanders had fallen off his horse. An arrow pierced the man’s lungs. Suddenly, Teushpa could hear cries and yells. Another man fell. A horse collapsed. Several others collided into one another.

And then the horsemen began to encircle them. Arrows flew in all directions. More men fell to the ground, embracing death.

It was at this moment Teushpa screamed. He rode forward. A few of his closest comrades followed suit. Teushpa knew not who these riders were. They rode with such acumen and such ferocity. They shot their arrows with such deftness and skill. These other horsemen, the ones slaughtering Teushpa’s men, were eerily similar to his own.

A creeping suspicion crawled on his skin. He turned to his comrades. He found only one still riding with him. The rest laid on the ground, peppered with arrows.

“The Scythae,” Teushpa uttered, recalling the name of the great invaders who had long since displaced the Kimmerians. Demons, they were. Monsters that hunted the Kimmerian ancestors and stole their land. Ungodly beings that ruined them over and over again. And then an arrow pierced his shoulder. And then another. And then Teushpa fell to the ground. Bleeding, he roared into the eternal blue sky.

The twilight of the Kimmerians had come. The nightmare of the Kimmerians had rode from the steppes and crossed through the mountains. The end of the Kimmerians was nigh. The Scythians entered the ancient Near East.

Welcome back to the Nomads and Empires podcast, episode 11. Once again, it has been a while, my bad on that. I’m at a new place, and I’m not sure how the audio is going to sound, so forgive me on all of this. But, to compensate, we’ll be talking about an interesting set of topics today, culminating in the near-end of our Kimmerian sojourn.

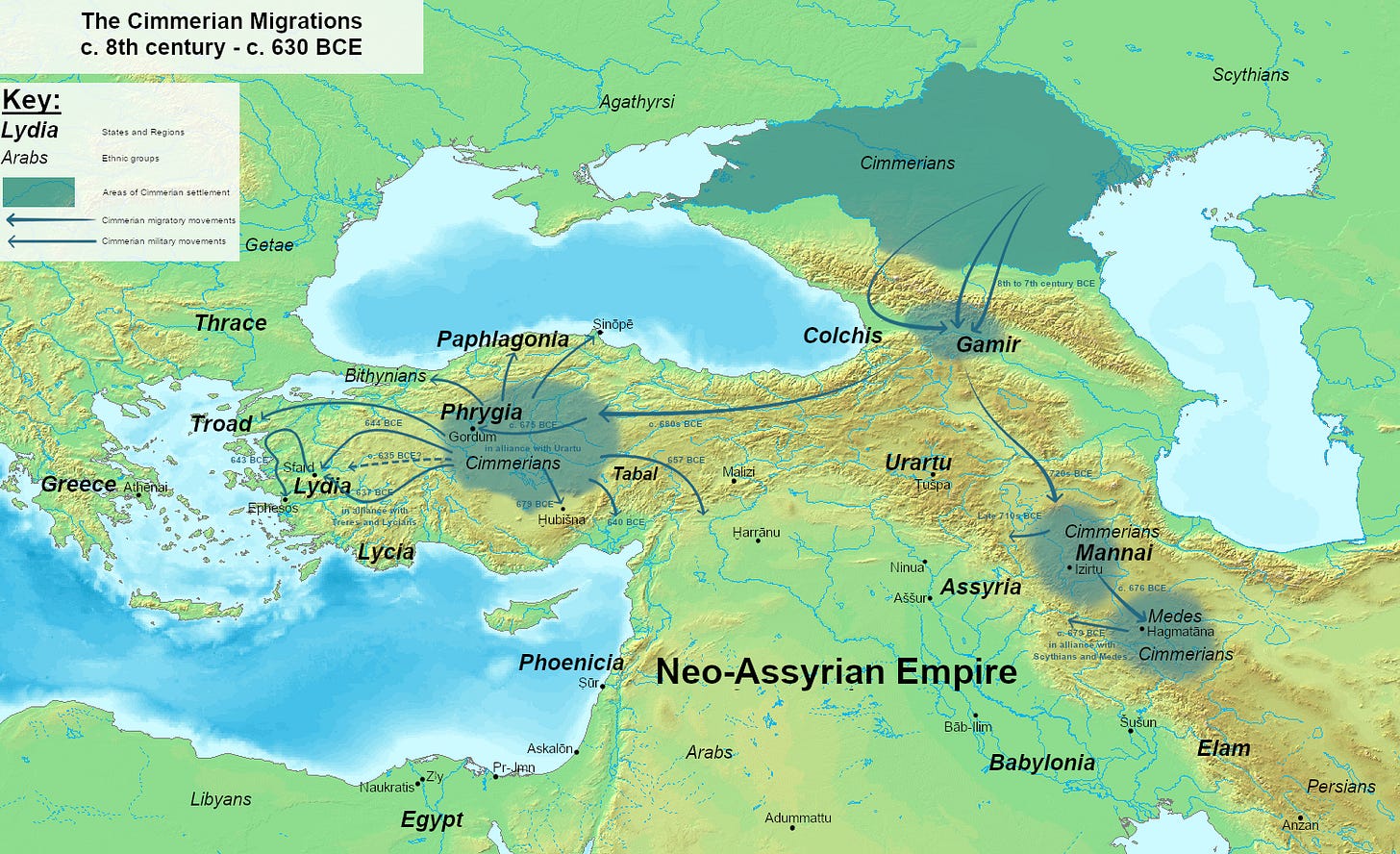

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Over the course of the last three episodes, we charted the rise of the Kimmerians, their migrations across the steppe and the Caucasus, and their political history in Anatolia and the ancient Near East. In the last episode, we dove deep into Kimmerian movements after the year 714 BCE. In the wake of invasions by the Urartians and the Assyrians, we hypothesized that the Kimmerians found themselves threatened and so, many chose to leave their pastures and migrate.This meant a retreat to the west, into the lands of the Anatolian Plateau. This placed the Kimmerians in a new land with new enemies. As such, from the 690s to the 680s, the Kimmerians raided the lands of the Kingdom of Phrygia, and Greek sources correlate their invasions with the death of King Midas.

In 679 BCE, the Kimmerians once again took to the offensive, trying to invade the lands of Assyria. The Assyrian king Esarhaddon was only two years into his rule, and it was a tenuous one at that. The Assyrian Empire had only just emerged from a disastrous civil war that ultimately led to Esarhaddon’s ascension.1 As such, the Kimmerians likely thought this was their opportunity to gain riches and even take vengeance on the Assyrians. Led by a chieftain named Teushpa, the Kimmerians attacked the Assyrians in a land called Hubushnu.2 However, Teushpa fell in battle and the Kimmerians were defeated. One Assyrian tablet refers to the event as a “slaughter” of the Kimmerians.3 Another Assyrian document recounts Esarhaddon’s own thoughts:

“And Teushpa, the Kimmerian, a barbarian whose home was afar off, I cut down with the sword in the land of [Hubushnu], together with all his troops.”4

And that’s where we last left off.

In the wake of this battle, we can imagine that the remnant Kimmerians bitterly crossed back into Anatolia. At this point, the exact areas of Kimmerian occupation are unclear. We can probably assume that some Kimmerian tribes operated in Phrygia given recent activity there. The invasion of Assyria points to some Kimmerian habitation in Cilicia as well.5 However, none of this is definitive, and I personally speculate that the Kimmerians at this point were operating as different tribal entities rather than as a unified people. Their geographic range would have been disparate and fluid, unlikely to be defined by strict borders.

In fact, the Encyclopedia Iranica reports to us that shortly after this battle, some Kimmerians could be seen in Assyrian armies.6 The Encyclopedia Iranica believes these Kimmerians to be slaves, likely taken from the battle of 679. However, we also noted in the last episode that some Kimmerian groups refused to migrate deeper into Anatolia, and those groups may have also joined the Assyrians as mercenaries.7

In any case, the next period of Kimmerian activity, at least until their invasion of Lydia around the 660s, is rather blurry. Some sources say that the Kimmerians entered an alliance with the Phrygians and aided them in an attack on the rival state of Melitene.8 This of course stands somewhat in contrast to other sources, which claim that the Kimmerians conducted another raid against Phrygia in 677, which led to the ultimate destruction of the city of Gordion.9 Meanwhile, Professor Mark Chahin asserts that the Kimmerians allied with the Urartians sometime in the mid-670s.10 This would supposedly result in an Urartian and Kimmerian joint attack on the state of Shurpia.11 To complicate things even further, an account from UNESCO’s History of Civilizations tells us that in 672, a combined Kimmerian and Scythian force helped the Medes in a rebellion against Assyria.12 As you can see, there’s a lot of potentially conflicting stories here, and I don’t feel comfortable weaving a cohesive narrative based on these accounts.

On one hand, it seems likely that various Kimmerian groups acted independent of one another, as we just discussed. This may be why we have such different recollections. One group could have lent support to the Phrygians, while another group may have been hell bent on destroying them. Some Kimmerians probably did act as mercenaries for the Urartians, just as others worked for the Assyrians. Again, the decentralized nature of various steppe groups could lend itself to this varying number of interactions.

However, I also think it’s likely that some of these narratives are completely wrong. We talked about the fuzziness of dates throughout the last few episodes, and it's definitely apparent here. The 670s are full of contradictions and missing information and are somewhat of a black hole.

So I’m not going to dwell too much on this. Let’s instead push on.

Given the flurry of activity mentioned before, we can at least assume that the Kimmerians were still active in raiding and looting various places across the Near East. A prayer attributed to the Assyrian leader Esarhaddon certainly points to this being the case. In this prayer, the Kimmerians are listed as one of many enemies that were plaguing the Assyrian Empire.

“O’ Shamash, great lord, whom I ask with true grace answer me! From this day, the third day of this month, Iyyar, to the eleventh month of Ab of this year, a period covering one hundred days and one hundred nights… In this time, will Kashtariti with his soldiers, or the soldiers of the [Kimmerians], or the soldiers of the Medes, or the soldiers of the Manni, or any enemy, as many as there are, have success with their plans? Will they either by overthrow or might, or by contest, battle, and war… seize the city of Kishassu?”13

And so, even if it isn’t clear where the Kimmerians were exactly in the 670s, they remained a problem on the Assyrian frontier. As we enter the 660-650s, Kimmerian movements become a bit more clear. Several sources, including Cunliffe and Beckwith both agree that the Kimmerians invaded the Kingdom of Lydia in 652, and that the Kimmerians were very active in that part of Anatolia for at least a decade prior.14 It would be here, in Lydia, where the Kimmerians would find great victories and terrible defeats that eventually set the stage for their decline.

But, before we get too deep into this series of events, let’s now take a slight detour and talk about the Kingdom of Lydia. The Kingdom of Lydia was another Anatolian polity. It was located to the west of Phrygia and was considered to be a pretty wealthy area. Located along the plains of the Hermus River (modern Gediz River), Lydia boasted a significant agriculture sector, was known for its abundance in cattle and horses, and was rumored to have significant gold deposits.15 By this point in time, Greek colonies like that of Ephesus were entrenched in the far western reaches of Anatolia, and so the Lydians were also known to have had a decent array of trade relations.16 However, the Cambridge Ancient History asserts that the Lydians were not seafarers, and it seems that the Greek colonies may have blocked naval access to the Lydians.17

Given this proximity to Greek colonies, Lydia would gain a notable reputation in the Hellenistic world. In fact, Herodotus recounts to us that the Kingdom of Lydia had a long and legendary history. In his account, by the 670s, a man named Gyges had launched a coup and taken the Lydian throne. Gyges would be similar to Midas of Phrygia in many ways. A legendary king of Anatolia with relations to the Greeks, Gyges would also be someone with his own share of legends. There is one particular story that is fascinating. Though the following account is likely ahistorical and somewhat of a tangent, I found it so interesting that I had to share this.

According to Herodotus, the dynasty that ruled before Gyges heralded from the lineage of the legendary Heracles.18 Led by a man named Candaules, Gyges at the time was merely a palace bodyguard. Gyges was considered to be Candaules’ best man, someone the king evidently favored. However, Hereodotus reports that Candaules was someone who really loved his wife and also really loved to show her off. Once, Candaules said to Gyges: “Gyges, I do not think that you credit me when I tell you about the beauty of my wife… Contrive, then, that you see her naked.”19 Gyges refused his master’s suggestion, arguing that it was amoral. Candaules however pushed on, and one night decided to lead Gyges into a room where Candaules’s wife was naked.

On one hand, Herodotus tells us that Gyges was shocked and shamed by the incident. However, Cadaules’s wife, who has continued to remain unnamed, was also outraged. According to Herodotus, “for among the Lydians and indeed among the generality of the barbarians, for even a man to be seen naked is an occasion of great shame.”20 The next day, Caudales’s wife ordered Gyges to appear before her. He entered her chambers and was given an ultimatum:

“Gyges, there are two roads before you. Either you must kill Candaules and take me and the kingship of the Lydians, or you must die straightaway, as you are, that you may not, in days to come, obey Caudales in everything and look on what you ought not. For either he that contrived this must die or you, who have viewed me naked and done what is not lawful.”21 Gyges was evidently frightened by the proposition, urging his king’s wife to forgo the plot and to forgive the wrong that had been done. She would not relent. Eventually, Gyges backed down and accepted the order. The two deliberated on details, and finally, Candaules’s wife gave the order:

“The attack on him shall be made from the self-same place whence he showed me to you naked, and it is when he is sleeping that you shall attack him.”22 She then provided Gyges with a dagger, and later that night, Gyges murdered his liege Candaules. In a swift coup, Gyges the bodyguard ascended to the throne, becoming Gyges, King of Lydia. Though now he sat comfortably on his throne, Gyges was now beset by a number of challenges.

To his west, Gyges was faced by a number of Greek colonies, and shortly into his reign, Gyges is said to have invaded the lands of Miletus and Smyrna, capturing the city of Colophon.23 Now, Herodotus makes the following claim: “However, no other great deed was done by him, although he reigned thirty-eight years, and so we will pass him by with just such mention as we have made.”24

This quick throwaway discussion of Gyges fails to account for the king’s full exploits. In thirty-eight years, Gyges evidently did much more than simply conquer a few Greek settlements. One of the other major challenges facing Gyges was the continued incursion of Kimmerian raiders, and it is here where we now turn to an interesting episode recounted in Assyrian records. As we may remember, sometime in the 690s (or 670s depending on your source), the Kimmerians defeated the Phrygians and sacked the city of Gordion. Phrygia had neighbored the kingdom of Lydia, and Gyges appears to have been concerned by these incidents. With Phrygia now weakened and unable to act as a buffer, Kimmerian raiders may have started infringing upon Lydian territory. Small raids and lightning-fast attacks could have occurred on the Lydian eastern frontier.

Gyges was faced with few options in dealing with the Kimmerian riders. Though he possessed a strong military, the Kimmerians were at their apex and seemed unstoppable. To some, it would take a miracle to prevent the nomadic riders from destroying Lydia. And so, one night, Gyges had a vision. In this legendary account, Gyges had dreamt of a great empire to the south and east, one that could help the Lydian king defeat the Kimmerians. Having no idea what this empire was, Gyges sent messengers in that general area, whereupon they met a delegation by none other than the Assyrian Empire. But, ya know, let me instead use the words of the Assyrian ruler himself. In a record left by Ashurbanipal, we are told the following:

“Gyges, king of Lydia, a district of the other side of the sea, a distant place, whose name, the kings, my fathers, had not heard, Ashur the God, my creator, caused to see my name in a dream. ‘Lay hold of the feet of Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria and conquer they foes by calling upon his name.’ On the day that Gyges beheld this vision, he dispatched his messenger to bring greetings to me. An account of this vision, which he beheld, he sent to me by the hand of his messenger, and made it known to me. From the day that he laid hold of my royal feet, he overcame, by the help of Ashur and Ishtar, the gods, my lords, the Kimmerians, who had been harassing the people of his land, who had not feared my fathers, nor had laid hold even of my royal feet.”25

In the wake of this meeting, messengers were sent back and forth, and soon Gyges developed a strong relationship with Ashurbanipal. The timing of this could not have come at a better time. Sometime later that year, the Kimmerians invaded, and Assyrian assistance allowed the Lydians to achieve a strong victory.26 As Ashurbanipal recounts: “From among the chieftains of the Kimmerians, whom [Gyges] had conquered, he shackled two chieftains with shackles, fetters of iron, manacles of iron, and sent them to me, together with his rich gifts.”27

And so, it would seem like the Kimmerians were once more put into a corner, with this Assyrian-Lydian alliance acting as a major block toward any Kimmerian advancement. However, Gyges was not content to be a junior partner and like many other ambitious rulers, he attempted to foster relations with other major powers. At some point between the 660s and 650s, Gyges tried to establish bilateral relations with the Egyptian Pharaoh Psammetichus.28 It is unclear if Gyges intended this as anti-Assyrian act or simply as an extension of his own international relations, but as we should know by now, the Assyrians valued loyalty over anything else, and so this act incurred the wrath of Ashurbanipal.29 In the Assyrian king’s own words:

“[Gyges’] messenger, whom he kept sending to me to bring greetings, he suddenly discontinued,-because he did not heed the word of Ashur, the god who created me, but trusted in his own strength, and hardened his heart. He sent his force to the aid of [the] king of Egypt… I heard of it and prayed to Ashur and Ishar, saying ‘May his body be cast before his enemy, may his foes carry off his limbs.’”30

In 657 or 652, Ashurbanipal’s curse appears to have come true, as the Kimmerians once more invaded the Lydians from the land of Cappadocia.31 The Assyrians offered no assistance, and the lands of Lydia were likely burned and raided. The secondary sources here are somewhat unclear on the exact timeline and sequence of events. The Encyclopedia Iranica tells us that Gyges and his kingdom survived the invasion on their own merit. The Cambridge Ancient History agrees with this assessment, noting that the Lydians continued to send military support to the Egyptians two years later.32 The Kimmerians would then invade again in the 640s and it would be here where the Kimmerians finally killed Gyges and destroyed the capital city of Sardis.33 Other sources, such as Barry Cunliffe, connect this invasion in the 650s with the downfall of Gyges, and so once again we must tread carefully when assigning hard dates to these events.34

Whatever the case may be, this point is clear: the Assyrians withdrew their support, opening up Lydia to a Kimmerian invasion. The Kimmerians invaded, and possibly invaded again. Gyges was killed, Sardis was ruined, and the Kimmerians were given free reign to rampage into western and southern Anatolia.

Again, Ashurbanipal’s records are quite clear on this: “The Kimmerians, whom [Gyges] had trodden underfoot… invaded and overpowered the whole of his land.”35

Gyges’ son Ardys ascended to the throne shortly after his father’s death. Recognizing his own father’s mistakes, Ardys sent messengers to the court of Ashurbanipal, seeking to restore the Lydian-Assyrian alliance.36 Ashurbanipal comments that Ardys’s messenger had pleaded for Assyrian support while bowing at Ashurbanipal’s feet.37

This desperation is likely Assyrian propaganda, but I think there is a large hint of truth in this account. The Lydian capital had been sacked, and we know the Kimmerians were still active in Lydian territory during the reign of Ardys.38 The Kimmerians probably continued to raid the Lydians, and during Ardys’ rule, we know of at least two concentrated invasions. The second of these invasions, which is dated to either 645 or 637, saw the emergence of a great coalition. The Kimmerians allied with a Thracian people known as the Treres and with an Anatolian people known as the Lycians.39 Sardis was once again sacked and looted, and Ardys may have perished in the fighting.40 Herodotus then recounts to us that the Kimmerians pushed westward, invading the Greek colonies of Ionia and Aeolis, and possibly even destroying the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.41

There is another curious timeline division that we should consider. In this final invasion of Lydia, which ultimately led to the destruction of Sardis, we are presented with two options on who led the Kimmerians: a man named Tugdamme or his son named Sandakhshatra. This is a really complicated subject, and I’m personally really excited for later historical groups that don’t have nearly as much drama or baggage when it comes to dates. But, we aren’t there yet, so let me be brief.

Sometime during Ardys’ reign, around the 640s, the Kimmerians began to raid northwestern Assyria. The Kimmerians were led by a man named Tugdamme, who the Assyrians called “the King of the Saka and the Gutium.”42 However, the Assyrians were able to broker an agreement of sorts, and Tugdamme offered tribute to the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.43 Tugdamme then broke this agreement not too long after, and once more the Kimmerians began to raid Assyria. In some sources, the Kimmerians even allied with the state of Tabal in anti-Assyrian operations.44

To quote Ashurbanipal again: “Tugdamme, king of the Umman-manda, offspring of Tiamat, the image of the devil, disregarded the oath by the gods by which he agreed not to do evil against, not to overstep the border of my land, and he was not in awe of thy honored name. To magnify thy sovereignty and the might of thy godhead, I overthrew him, according to thy divine message which thou didst send, saying: ‘I will destroy his power.’ Sandakhshatra, the son, offspring of his loins… they had put in his place.”45

In reality, the Assyrians likely did mount a defense against Kimmerians raids, but Assyrian military might was not what led to Tugdamme’s fall. Illness was. Sandakhshatra then took his father’s place and continued to lead Kimmerian military operations. And here, we must go back to the second invasion of Lydia during the reign of Ardys.

Essentially, the timeline could be as follows: Tugdamme led the Kimmerians in two invasions of Lydia against Ardys. Tugdamme may have developed relations with the Lycians and the Treres to create this coalition. Then, having accomplished the destruction of Sardis, Tugdamme led the Kimmerians to Cilicia and began to raid the Assyrians. Then the story we just heard occurs. The other option is thus: After killing Gyges, Tugdamme led the Kimmerians into Cilicia. From there, they raided Assyria, began to offer tribute, and then reneged on the treaty. Tugdamme then perishes from illness, and Sandakhshatra, perhaps fearing Assyrian military might, moved back to Lydia and invaded the lands of Ardys with assistance from the Lycians and the Treres.

So, those are our two options. I don’t think either of these options affect our narrative, but I wanted to give both academic perspectives before moving on.

The Kimmerians continued on with their raids. If we assume 637 BCE to be the second invasion under the reign of Ardys, then Ardys would be succeeded by his son Sadyattes. Sadyattes would not reign long. The Cambridge Ancient History gives Sadyattes five years to his rule. Other sources only give him two. In such time Sadyattes is known to have conducted a series of raids against a people known as the Milesians, but he is otherwise unnoteworthy.46 The only other point to make is that some speculate Sadyattes to have perished in a Kimmerian attack.

And now, we reach closer to the end of the Kimmerians. Throughout this episode, the Kimmerians really have felt like a menace, devastating many of the Near Eastern polities and participating in lightning-fast raids. What I haven’t covered yet are the movements of the Scythians. Yes, we noted that some Scythians participated in a few battles against the Kimmerians, but now a concentrated population of Scythian riders were manifesting in the Ancient Near East. Madyes, son of the Scythian chief Bartuta, was waiting in the distance for his own opportunities. In fact, Madyes and the Scythians were off fighting the Medes, and we’ll visit their perspective soon. But, now, the Scythians were very aware of Kimmerian activity.

At the same time, the death of Sadyattes opened the door for his own son Alyattes. Alyattes would become one of the greatest rulers in Lydian history. Alyattes would expand Lydian hegemony across Anatolia. He would subdue the western Greek colonies.47 He would become master over large swathes of Phrygia.48 He would produce some of the earliest coins in recorded history and he would play a decisive role in ending the Kimmerian menace once and for all.49 It would be Alyattes and Madyes, Lydian and Scythian, who would finally put an end to the Kimmerians.

But, that is for another time. Instead, I wanted to take the remainder of this episode to quickly recap the events we just mentioned. Given the disparate timelines and differing dates, I know this was probably harder to follow than other episodes, and so to accommodate this, I’ll offer my own sequence of events. Remember, dates are fuzzy and some events probably did happen at other points and in different orders. I just want to put things in some sequence so that we have an understanding of how these individual events will come together in the next episode.

We started this episode by assessing the Kimmerian situation after their failed invasion of Assyria in 679. Between 679 to the mid-660s, our understanding of Kimmerian history is unclear. Different authors cite different events at different times, and to my mind, none of that is conclusive and should be taken as speculation. Instead, the next key event comes in the mid-660s, when Gyges of Lydia sends envoys to the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal. The Kimmerians had probably threatened the Lydians by this point through a series of raids, and the Lydians and the Assyrians soon developed an anti-Kimmerian agreement. However, Gyges’ support for the Egyptians eventually led to the end of this alliance. In 657 or 652, the Kimmerians invaded, devastated the capital city of Sardis, and may have killed Gyges. The Kimmerians invaded once more in 644. There remains debate on whether Gyges perished in this invasion, or if this represented the first incursion under Gyges’ son Ardys. A final invasion in 637 led to the destruction of Sardis and possibly the death of Ardys. Sometime before this invasion or shortly after, the Kimmerians moved into Cilicia and engaged in diplomatic relations with the Assyrians. Again, not really sure which is the case.

And that, my friends, is the timeline we examined. I won’t lie. It was quite confusing for me as well, and I’m certain I made mistakes in trying to piece this together. As always, please send me any corrections and other feedback via Twitter or my email. I also wanted to apologize for the delay on this episode. A lot continues to happen in my life. Luckily, all of it is good stuff, but it does mean that I am slower in producing this podcast. Sorry!

But, with all of that said, I think we’re done here. Next time, we actually, legitimately, finally get to the end of the Kimmerians. The Scythians, the Lydians, the Assyrians and other powers would conspire together to oust the people of Kimmeria. And then, they would be no more. So, tune in next time, and I’ll see everyone of you on the desolate grasses of the Anatolian Plateau.

J. A. Delaunay, “ASSARHADDON,” Encyclopædia Iranica, V/2, 803-805.

“ABC 14 (Esarhaddon Chronicle),” Livius.

Ibid.

Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume II, Historical Records of Assyria from Sargon to the End, trans. David D. Luckenbill (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1927), 206.

Sergei R. Tokhtas’ev, “CIMMERIANS,” Encyclopædia Iranica, V/6, pp. 563-567, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cimmerians-nomads.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Barry Cunliffe, The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2019), 33.

Mack Chahin, The Kingdom of Armenia: A History (Curzon Press: Surrey, 2001), 97.

Ibid, 98.

M. A. Dandamayev, “Media and Achaemenid Iran,” in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. 2: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B.C. to 250 A.D., (UNESCO Publishing: New York, 2010), 37.

Assyrian and Babylonian Prayers,” trans. Robert Francis Harper, University of Chicago, 284.

Christopher J. Beckwith, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2009), 62; see also Barry Cunliffe, The Scythians, 33.

M. Mellink, “The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia,” in The Cambridge Ancient History III, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1991), 644; see also, Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, “Lydia and Phrygia,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Alan M. Greaves, “The Greeks in Western Anatolia,” in The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: 10,000–323 B.C.E (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011), 504.

M. Mellink, “The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia,” 644.

Herodotus, The History, trans. David Greene (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1987), 36.

Ibid.

Ibid, 37.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid, 39.

Ibid.

“Assyrian and Babylonian Prayers,” 297-298.

Sergei R. Tokhtas’ev, “CIMMERIANS.”

M. Mellink, “The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia,” 645.

Anthony Spalinger, “The Date of the Death of Gyges and Its Historical Implications,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, no.98, (1978), 403.

Sergei R. Tokhtas’ev, “CIMMERIANS.”

M. Mellink, “The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia,” 645.

Sergei R. Tokhtas’ev, “CIMMERIANS.”

Ibid.

M. Mellink, “The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia,” 647.

Anthony Spalinger, “The Date of the Death of Gyges and Its Historical Implications,” 406.

M. Mellink, “The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia,” 647.

Ibid.

Herodotus, The History, 35.

Anthony Spalinger, “The Date of the Death of Gyges and Its Historical Implications,” 407.

Ibid.

Sergei R. Tokhtas’ev, “CIMMERIANS.”

Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume II, 385.

M. Mellink, “The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia,” 647.

Ibid.

Lynn E. Roller, “Phrygia and the Phrygians,” in The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: 10,000–323 B.C.E (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011), 564.

G. Kenneth Sams, “Anatolia: The First Millennium B.C.E. in Historical Context,” in The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: 10,000–323 B.C.E (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011), 613.